During my first-ever trip to England, my husband and I travelled to Cornwall to see Colin Wilson, one of the country’s most reclusive writers. Known for his often tumultuous relationship with the press, I wasn’t sure of our reception, but once we were there, what began as an exclusive interview for The Ottawa Citizen quickly turned into the following full-page feature!

He was an extraordinary man living what had become, in many ways, the most ordinary existence on the coast of Cornwall with his wife of 40 years, their two dogs and an aging parrot. If it weren’t for the 30,000 books, tapes and records covering every available surface and the Japanese interviewers in the living-room, one might easily assume that the couple in question had merely settled down for a lengthy retirement in this tiny coastal town…

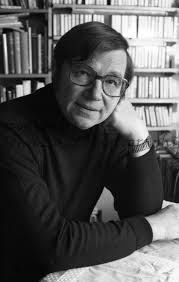

Portrait courtesy of photographer John Lyne

But this is Colin Wilson, one of Britain’s pre-eminent “angry young men” who first rose to prominence in the 1950s, taking on both the establishment and the scions of the literary press at the age of 24 with The Outsider, a bold and challenging look at the way we perceive human consciousness. One hundred books later, Wilson still annoys and confounds the critics with his “obsessive quest for something grander than normality” that all began with his own feeling of isolation on Christmas Day, 1954.

Joy, who at that time was still his girlfriend and not yet his wife, was at home with her parents, and Wilson, who had neither the money nor the inclination to spend the holidays with his, was living in a room in Brockley, a South London suburb. Amidst this self-imposed isolation – and a Christmas dinner of canned tomatoes and bacon – he felt both cut off from the rest of society and at one with some of his favorite fictional heroes, like Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov, Camus’s Meursault and Sartre’s Roquentin. The notes he compiled that Christmas Day in his journal became the starting point for his most famous book, and the catalyst for both his “overnight success” and his subsequent fall from grace.

What makes Wilson’s story so interesting is that, unlike the other “angry young men” of the decade – writers such as John Osborne, John Braine and Kingsley Amis – Wilson had no formal education. And the critics found that offensive. The novelty soon wore off, and the darling of the previous year became the literary pariah of the next. Wilson claims that his own sense of self-worth and belief in his theories of human consciousness are what sustained him. For, as he wrote in the 1967 edition of The Outsider, he held “the final card.” He was used to working in a vacuum, which meant that he could go on writing longer than his critics could “go on sneering.”

And sneer they did. Book after book after book. Especially in England, where the publication of his first novel, Ritual in the Dark, was met with derision and the praise that had been heaped upon the young Wilson the year before was taken back. The “boy genius” was a charlatan, and when Joy’s father came to London with a horsewhip to rescue his unwed daughter from the man he considered a sexual pervert, the press had a field day. Colin and Joy fled London and the gossip that dogged their heels as they travelled throughout Devon, Ireland and Wales.

It’s a story Wilson enjoys telling, and one can tell by the inflections in his voice that it’s one he’s told many times before to visitors like myself who are curious about the man who has ostracized himself from the mainstream, continuing to work away year after year, proving his own theories on human consciousness and compiling one of the most impressive bibliographies that this century has to offer.

Although sitting in his living-room in Cornwall, eating smoked salmon and drinking a glass of white wine, I find it hard to reconcile  such a “literary outsider” with the 67-year-old Wilson before me.

such a “literary outsider” with the 67-year-old Wilson before me.

He is above all, one of the most hospitable people I’ve ever met. When he heard Richard and I would be in England on a working holiday he immediately invited us to join him and his wife for dinner and drinks. Drinks at 5:00 are part of their regular routine, he explained, an oasis in a day that starts at 5 a.m. and goes steadily until 4:00 in the afternoon when he breaks to walk the dogs and reflect on the progress of the day.

It was foggy the night we arrived in Gorran Haven, the fishing hamlet on the coast of Cornwell where Colin and Joy have lived since 1958, and although we weren’t officially expected until the next evening, they insisted we come round for “drinks” when we called to say that we’d arrived.

The bed-and-breakfast we were staying in was just up the road, so we agreed, but given the weather and the steep, narrow roadway that to my Canadian eyes appeared to be little more than an asphalt bike path, we decided to drive the half-mile to the Wilsons’. With Richard at the wheel, we cautiously wove our way downhill in second gear, peering through the mist for the small sign marking the entrance to “Tetherdown.”

The laneway to the Wilson’s house is like a tunnel to the unknown, with its overhanging trees and shrubbery left untrimmed to discourage unwanted visitors. The house itself, a rambling bungalow built into the slope of the hill, looks and feels like the hideaway it is meant to be, for Colin Wilson has no interest in establishing relationships with his neighbours. They may be quite nice but he wants to avoid the type of “obligatory dinner parties” that seem to be the norm for many of the retirees living in the frost-free regions of southwestern England. He does, however, maintain a vast network of friends around the world, communicating by phone and fax, regular post and email, with colleagues in such far-flung places as Japan, Australia, the United States, Russia and Spain, many of whom have followed his career since The Outsider was first published.

It was already gone 5:00 when we returned to Tetherdown the next day to find Joy, wearing her rain gear, heading at a pretty fair clip in the opposite direction. Richard stopped the car beneath the sodden bushes and rolled down his window. There had been a fire, Joy said. In her bedroom. Lightning had hit the telephone line at the outside junction and burned out the modem attached to the computer in her room, setting the bed on fire and destroying her books.

But not to worry, she was on her way to use the telephone at the old folks’ home across the way. The fire department had already been and she had to get on to the insurance people right away. As for cancelling the evening, Joy would hear nothing of it. They had to eat, she said, and scurried off down the laneway, leaving us dumbfounded at the casual way she was handling what to us, was an incredible disaster.

It was the relief, you see, explained Colin once we were settled inside, that nothing more had happened. Another minute and the fire would have spread throughout the house, and in their location, with the nearest fire brigade stationed miles away and nearly a score of other fires needing their attention that afternoon, they were lucky to receive any help at all – the usual method of dealing with a fire in the area was to let it burn itself out and then call the insurance man. Luckily, he and Joy had been able to contain the fire with buckets of water and a garden hose until help arrived.

It’s this attitude that, for me, typifies Wilson’s approach to life. The sheer wonder of what is, and the clarity that comes with an epiphany, that moment in time when everything is suddenly pristine and joyous.

It is a theory Wilson happened upon when he was a young man. He’d been hitch-hiking to Peterborough, near Oxford, depressed and anxious about his lot in life, when a truck driver stopped and offered him a ride. After a mile or so, a knock developed in the gear box, and the driver let Wilson out while he went in search of a garage. Wilson stuck his thumb back out, and a second trucker stopped and picked him up. Several minutes later, he too developed a knock in his engine. And Wilson, who hadn’t wanted to make the trip in the first place, suddenly found himself wanting to get there so badly that when the driver discovered that the knocking would stop if they kept their speed below 20 m.p.h., he was overjoyed.

Wilson’s feelings of relief were so overwhelming, and so absurd given his earlier attitude, that he realized he had stumbled upon what was to be his first important observation as a philosopher – “that man’s moments of freedom tend to come under crisis or challenge, and that when things are going well, he tends to allow his grip on life to slacken.” He refers to this phenomenon as the “St. Neot margin” after the town they were driving through at the time. And, half a lifetime later, he’s as fascinated by this heightened state of consciousness as he was then, still exploring ways to recapture the St. Neot margin at will and use it to his advantage.

The difference between Colin Wilson’s attitude as a “new existentialist” and the romantics of the previous century is that unlike the romantics, who found everyday life miserable and dispiriting, Wilson has always been an optimist. For him, “moments of vision” in which everything is marvelous and exciting, are reason to celebrate, to look beyond what is known, a theme he has continually explored in all his works, and one of the reasons he ventured into another realm of the unknown in 1971 with The Occult, his controversial look at ways to extend the boundaries of human consciousness and further develop our capabilities.

Wilson’s unique way of approaching a subject keeps him in print year after year, and keeps his publishers ever anxious for the next Colin Wilson. Even the gestation of his books, the where and how behind his ideas and the way they manifest themselves on the page makes for fascinating reading. Written in Blood, his encyclopedic tome on the evolution of forensic detection is a case in point.

Wilson was at a reception in Tokyo in 1986 when someone introduced him to Soji Yamazaki, the executive editor of the Mainichi News. In his younger days as a crime reporter, Yamazaki had covered the criminal findings of Japan’s real-life Sherlock Holmes, an inspector by the name of Asaka Fukuda. Fukuda had apparently developed his reputation through his ability to differentiate between what looked like a suicide and what was, in reality, a murder. Wilson was intrigued, and when he got a call from his publisher on his return home, asking him whether or not he would be interested in writing a history of criminal detection, he was hooked. The result is one of the most comprehensive histories of the way modern scientific application and dogged investigative procedures have changed our lives.

Wilson’s strength is in “connecting the dots”, in interpreting what others have found and looking for the “universality” in their discoveries – a method that led to his most recent book, From Atlantis to the Sphinx. His “own part in the quest” began nearly 20 years ago when, in July 1979, he received a review copy of a book called Serpent in the Sky, by John Anthony West.

“It was basically a study of the work of a maverick Egyptologist called Rene Schwaller de Lubicz,” writes Wilson, “and its central argument was that Egyptian civilization – and the Sphinx in particular – was thousands of years older than historians believe.”

Schwaller de Lubicz’s theory was that it was water, and not wind and sand as is generally accepted, that caused the erosion of the body of the Great Sphinx at Giza. Wilson says that, if proven correct, Schwaller’s theory would not only “change all accepted chronologies of the history of civilization; it would force a drastic re-evaluation of the assumption of progress.”

The possibility that a sea-faring civilization existed before the Egyptian dynasties – indeed, before the Ice Age – a civilization that operated on a knowledge system based on instinct rather than information, intrigued Wilson. He felt, as did Schwaller, that the ancients must have had a heightened consciousness that allowed them to perform technological feats beyond our understanding, and that this holistic approach to understanding the universe was passed on through their descendants to other parts of the world, allowing them to develop in parallel fashion.

Working with ancient sea maps, called portolans, researchers concluded that when Antarctica was free of ice, it was at the centre of a worldwide maritime civilization, a possible Atlantis that flourished until about 10,500 B.C. After a series of catastrophes, the earth’s crust shifted and Antarctica drifted towards the pole, leaving its survivors with their navigational skills and their ability to work as “a collective” to spread their culture to the land masses to the east and west. Hence the similarities between, for example, the Aztec temples in Central America and the Great Pyramids of Egypt an ocean away.

Interest is so high in this field that the Discovery Channel in the U.K. commissioned a documentary based on Wilson’s book and Schwaller’s theories. The Flood, which recently aired in North America, is hosted by Wilson and in the rough cut we saw, he proves to be extremely effective on camera, giving an air of learnedness that is both comfortable and vaguely reminiscent of an Attenborough or a Carl Sagan. In measured tones, Wilson walks the viewer through his theories and those of his colleagues, Robert Bauval, Charles Hapgood and Graham Hancock, with the assuredness of a host who knows his subject.

Quick-tempered, profane, brilliant, warm, loving – these words all describe the Colin Wilson we saw during the time we spent with him, and his wife. His children visit frequently, as they did the weekend we were there. A self-described “domestic animal,” Colin was enormously proud of his new grandchild and extremely affectionate, not afraid to show emotion in front of guests, hugging his adult son and calling him “baby.” It’s a life that is both orderly and chaotic, open to visitors yet closed to the immediate neighbours.

Involvement in the local community is left to Joy – she wrote two local histories some years ago and is currently at work on another – while Colin does the weekly drive to either Truro or St. Austell for groceries and any other household needs not readily available in Gorran Haven.

Nestled at the base of a cliff, and continually buffeted by storms and high waves rolling in from the English Channel, Gorran Haven is an odd collection of fishing boats and skiffs, very different from the quaint shops and tourist spots found in other areas of Cornwall yet able to draw its own share of the sightseeing crowd with tales of smuggling and spectacular scenery. The local pub plays host to the usual mix of regulars and holiday-makers with its low ceilings and brass-railed bar, and in a rare show of public support – somewhat self-serving, red wine drinker that he is – Colin Wilson cut the ribbon at the Llawnroc Hotel when the town repealed its temperance laws and the pub was allowed to open.

As with everything Wilson does, there’s controversy. Even now, in the age of electronic debate, a website devoted entirely to his writing is rife with discussion, pro and con, about Wilson and his work; whether or not his current theories on evolution and consciousness are consistent with his earlier findings, and whether or not he is still a force as we approach the millennium. The general consensus online is that Wilson remains one of the most important writers and thinkers of the day, high accolades for a man who has spent his life working from an academic distance of time and geography – without the restrictions of a particular school of thought or the pressure to protect his “tenure” by presenting his findings in any of the accepted versions.

For Wilson is a consummate academic. Though self-taught – he dropped out of school at the age of 16 to work in a Leicester factory like his father – he has encyclopedic knowledge and can quote at will from the likes of Shaw, Graham Greene, Blake, Eliot and Rilke, Nietzsche and Jung.

In his 1990 biography, Colin Wilson: the Man & His Mind, Dosser reinforces the claim that Wilson’s lack of formal education is one of the prime reasons critics take such exception to his theories and view him as a threat to modern philosophy. And he is convinced that, in the next century, critics will be puzzled by the lack of attention bestowed upon Wilson by his contemporaries and give him his rightful due. Given the amount of attention Wilson already receives from other parts of the world, Dossor’s probably right.

Wilson’s books on the occult, on crime, on human sexuality and on the evolution of mankind have been translated into Spanish, French, Swedish, Dutch, Japanese, German, Italian, Portuguese, Danish, Norwegian and Hebrew.

Not bad for a working-class boy who defied both the odds and the critics to become one of the most talked about, and read, philosophers of our time.

Colin Wilson died, aged 82, on the 5th of December, 2013, but his legacy lives on at the University of Nottingham where, in July, 2016, the university’s Manuscripts & Special Collections department hosted The First Colin Wilson International Conference.

With special thanks to photographer John Lyne: http://www.johnlyne.com/